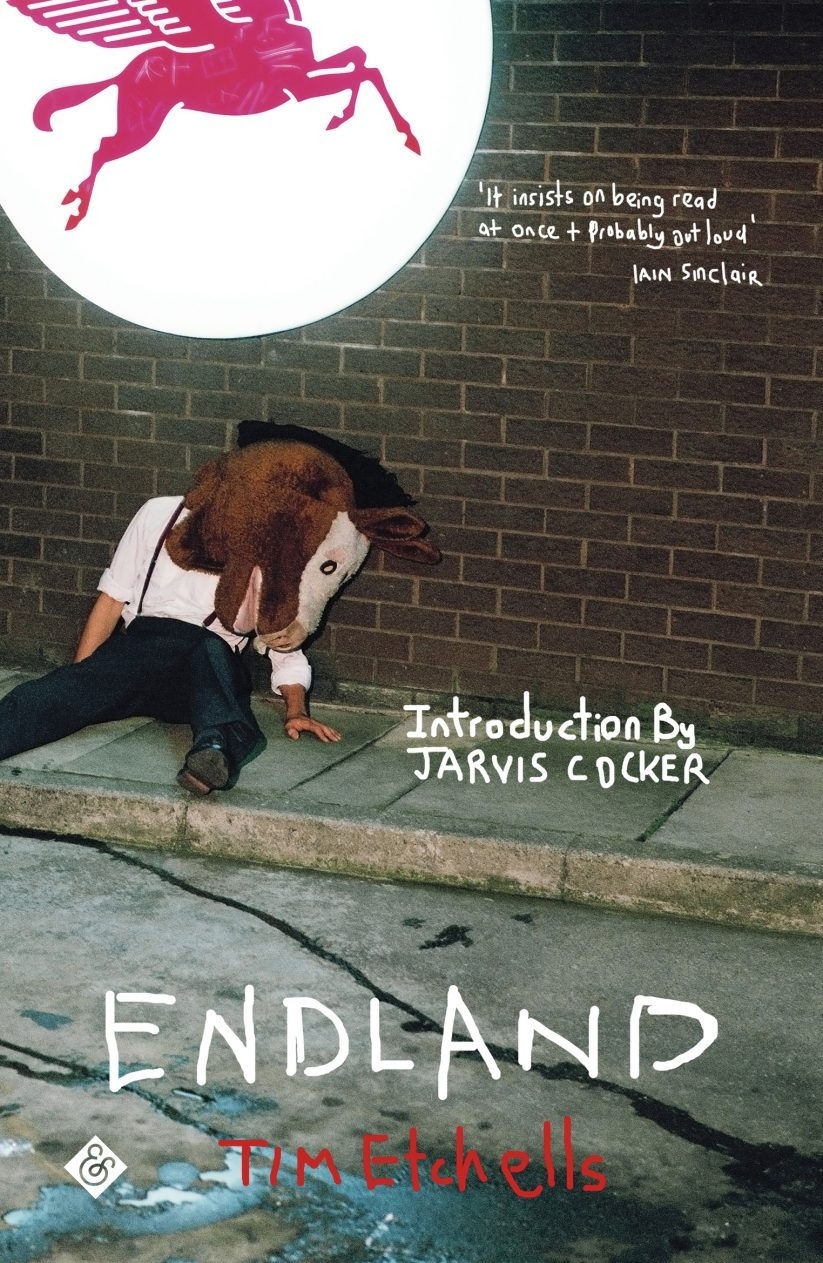

Endland by Tim Etchells

- Nicole Burke

- May 28, 2020

- 4 min read

‘And the Gods looked down on Endland (sic) and tbh they were pretty unhappy how it turned out. […] Was it humanity itself or only capital that was to blame?’

- Tim Etchells, Endland

Tim Etchells, writer, artist, and Professor of Performance and Writing at Lancaster University once exhibited an art piece called ‘the future will be confusing,’ in Frankfurt, Germany. This concept has been explored even further in Endland, a bizarre and dreamlike collection of urban myths and legends. Endland is England in the past, present, and future. The three are inextricable from each other, and this anthology illustrates Marx’s thesis in Das Kapital (1867), that one must simply pay attention to history in order to divine what is to come in the future. “How?” I hear you ask, well please continue reading to discover more!

In a previous work, Vacuum Days, published in 2012, Etchells ‘explores the zone of sensationalist media, news-as-pornography, hyped up current affairs, Internet spam, twitter gossip and tabloid headlines,’ as stated on his website. In Endland, however, he creates a collage of proletariat melancholy set in what can only be described as a dystopian theme-park. It is written in the vernacular of societies overlooked and forgotten. It is not written in standardized English but lived English. The language in Endland is a breathing, living organism.

Composed in a very distinctive British gallows humour, the reader is introduced to a mixed bag of characters, including Taggy, in the story “Taxi Driver,” who lives a Sisyphean nightmare in which he is chained to a rock and eagles devour his liver each night. We encounter deities named Scaletrix, Rent Boy, Herpes, Porridge, Spatula, and Lucozade, the king of the gods. The reader is invited to take part in the fun of QUIZOOLA, Endland’s beloved quiz show, featuring regular captains Fred and Rosie West. Marion and Tigar perform puppet shows with an apocalypse occurring in the background in “The Waters Rising.” Many of these stories are set in the backdrop of some unnamable armed conflict, which is always threatening to spill over into the protagonist’s lives. In “The life, movies and short times of Natalie Gorgeous,” the titular character sings ‘we’re in a strange land baby, and going to a worse land…’ Indeed.

In an interview with Jennifer Hodgson with the Quietus, Etchells declared that ‘reality is too important to be left to the realists.’ One may read Endland as a series of surreal and absurdist urban parables; a poetic understanding of contemporary existence. Or one could read it with some context in mind. Certainly, in the post-Brexit timeline we currently inhabit, it is very difficult to divorce Endland from its historical moment. Like all art, it was not created in a vacuum.

Endland is an agonizing hangover from Thatcherism, better known as neoliberalism. Margaret Thatcher’s legacy as Prime Minister of the UK from 1979 to 1990 was the introduction of the new age of market forces and explicit individualism that has atrophied state funding towards those who need it the most, including jobs and housing. Her policies were similar to those of Ronald Reagan, who was President of the United States from 1981 to 1989. Under these leaders, capitalism was inaugurated as, not just the dominant economic system, but the only viable one, clarified by TINA – There Is No Alternative. The results of these policies are still moulding Britain’s politics today.

Throughout Endland the reader is brought backwards and sideways through time, but never forwards. Indeed, the Thatcher years and their lasting effects are a chronology of their own; an alternate timeline where the gap between the rich and the poor is truly evident. For example, in the story “They get you most of all gone when you always alone,” Etchells dramatizes the increasing poverty in the global North. In this story, he frames a view of those on the poverty line as living in a ‘fabled Wildlife.’ Those who live there are a tribe of women and men who were “addicted to poverty, […] deep down less than humans.” This is a discourse that is often propagated by those who are in an economically powerful position in order to characterise poverty as a personal lifestyle choice, rather than a systemic condition of neoliberal capitalism.

The late—and great—cultural theorist Mark Fisher argued that neo-liberalization has left us ‘with a yearning for a future where a future cannot be delivered,’ in a talk titled “The Slow Cancellation of the Future.” In Endland, this is taken to the extreme. For each step forward our leading characters take, they take two backwards. In “Shame of Shane,” the titular character lives a whole lifetime, yet remains 25 years old, in a ‘future endless’ exclusive to the inhabitants of Endland. We can blame this fissure on the structure of time on the anarchic duo in “Cellar Story,” in which Curtis Thumb and his grandson Andrew craft a bootleg version of Schrodinger’s experiment (you know, the one with the cat in the box).

In the story “Long Fainting/ Try Saving Again,” 12 year old Gina accidentally uploads herself to the internet, and disappears from her family home for nearly a decade, until she eventually reappears at the age of 20. When questioned about her time away, Gina vaguely replies that ‘the past was a locked room [...] a topic not to be mentioned.’ After failing to re-adjust to physical reality, she returns to the virtual realm. By refusing to acknowledge the past, Gina repeats it.

With the effects of Thatcherism still moulding Britain to this day; it is equally as difficult to imagine the reality of Brexit removed from the political history it is a part of.

There is an infectious nihilistic force pervading through each story in Endland, mingled with a Camus-inspired, absurdist wit. These fables of neoliberalism are sure to provoke thoughtful reflection upon reading. The playfulness with language and creativity in representing the gloomy reality that many people have no choice but to live their lives is an exciting approach to art. To quote Olivia in the story “James,” ‘it is not about something, it is something.’

Endland

By Tim Etchells

352 pages. 2020.

代发外链 提权重点击找我;

google留痕 google留痕;

Fortune Tiger Fortune Tiger;

Fortune Tiger Fortune Tiger;

Fortune Tiger Slots Fortune…

站群/ 站群;

万事达U卡办理 万事达U卡办理;

VISA银联U卡办理 VISA银联U卡办理;

U卡办理 U卡办理;

万事达U卡办理 万事达U卡办理;

VISA银联U卡办理 VISA银联U卡办理;

U卡办理 U卡办理;

온라인 슬롯 온라인 슬롯;

온라인카지노 온라인카지노;

바카라사이트 바카라사이트;

EPS Machine EPS Machine;

EPS Machine EPS Machine;

EPS Machine EPS Machine;

무료카지노 무료카지노;

무료카지노 무료카지노;

google 优化 seo技术+jingcheng-seo.com+秒收录;

Fortune Tiger Fortune Tiger;

Fortune Tiger Fortune Tiger;

Fortune Tiger Slots Fortune…

站群/ 站群

gamesimes gamesimes;

03topgame 03topgame

EPS Machine EPS Cutting…

EPS Machine EPS and…

EPP Machine EPP Shape…

Fortune Tiger Fortune Tiger;

EPS Machine EPS and…

betwin betwin;

777 777;

slots slots;

Fortune Tiger Fortune Tiger;

google 优化…

Fortune Tiger…

Fortune Tiger…

Fortune Tiger…

Fortune Tiger…

gamesimes gamesimes;

站群/ 站群

03topgame 03topgame

betwin betwin;

777 777;

slots slots;

Fortune Tiger…

谷歌seo优化 谷歌SEO优化+外链发布+权重提升;

456bet 456bet;

google 优化 seo技术+jingcheng-seo.com+秒收录;

谷歌seo优化 谷歌SEO优化+外链发布+权重提升;

Fortune Tiger Fortune Tiger;

Fortune Tiger Fortune Tiger;

Fortune Tiger Fortune Tiger;

Fortune Tiger Slots Fortune…

gamesimes gamesimes;

站群/ 站群

03topgame 03topgame

betwin betwin;

777 777;

slots slots;

Fortune Tiger Fortune Tiger;

google seo…

03topgame 03topgame

gamesimes gamesimes;

Fortune Tiger…

Fortune Tiger…

Fortune Tiger…

EPS машины…

Fortune Tiger…

EPS Machine…

EPS Machine…

EPP Machine…

EPS Machine…

EPTU Machine…

EPS Machine…

seo seo